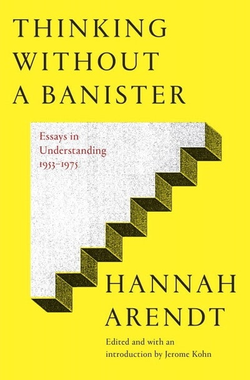

Hannah Arendt - Thinking Without a Banister: Essays in Understanding, 1953-1975

| Dear Hiveans | Liebe Hiver | Queridos Hiveanos |

|---|---|---|

| Today I'd like to share my favourite excerpts from the book "Thinking without a Banister" (goodreads) by Hannah Arendt, who was a German-American political theorist. Her work deals with the nature of power, authority, and totalitarianism. "Arendt is the most original and provocative thinker of the 20th centuy" (Michael Ignatieff). | Heute meine Lieblingsauszüge aus dem Buch "Denken ohne Geländer" (goodreads) von Hannah Arendt, einer deutsch-amerikanischen politischen Theoretikerin. Ihr Werk beschäftigt sich mit dem Wesen von Macht, Autorität und Totalitarismus. "Arendt ist die originellste und provokanteste Denkerin des 20. Jahrhunderts" (Michael Ignatieff). | Hoy me gustaría compartir mis extractos favoritos del libro "Pensar sin barandilla" (goodreads) de Hannah Arendt, teórica política germano-estadounidense. Su obra trata de la naturaleza del poder, la autoridad y el totalitarismo. "Arendt es la pensadora más original y provocadora del siglo XX" (Michael Ignatieff). |

Marxism

Through Marxism Marx himself has been praised or blamed for many things of which he was entirely innocent; for instance, for decades he was highly esteemed, or deeply resented, as the “inventor of class struggle,” of which he was not only not the “inventor” (facts are not invented) but not even the discoverer. More recently, attempting to distance themselves from the name (though hardly the influence) of Marx, others have been busy proving how much he found in his avowed predecessors. This searching for influences (for instance, in the case of class struggle) even becomes a bit comical when one remembers that neither the economists of the 19th or 18th centuries nor the political philosophers of the 17th century were needed for a discovery of what was already present in Aristotle.

It has become fashionable during the last few years to assume an unbroken line between Marx, Lenin, and Stalin, thereby accusing Marx of being the father of totalitarian domination. Very few of those who yield to this line of argument seem to be aware that to accuse Marx of totalitarianism amounts to accusing the Western tradition itself of necessarily ending in the monstrosity of this novel form of government. Whoever touches Marx touches the tradition of Western thought; thus the conservatism on which many of our new critics of Marx pride themselves is usually as great a self-misunderstanding as the revolutionary zeal of the ordinary Marxist. The few critics of Marx who are aware of the roots of Marx’s thought therefore have attempted to construe a special trend in the tradition, an occidental heresy that nowadays is sometimes called Gnosticism, in recollection of one of the oldest heresies of Catholic Christianity. Yet this attempt to limit the destructiveness of totalitarianism by the consequent interpretation that it has grown directly from such a trend in the Western tradition is doomed to failure. Marx’s thought cannot be limited to “immanentism,” as if everything could be set right again if only we would leave utopia to the next world and not assume that everything on earth can be measured and judged by earthly yardsticks. For Marx’s roots go far deeper in the tradition than even he himself knew. I think it can be shown that the line from Aristotle to Marx shows both fewer and far less decisive breaks than the line from Marx to Stalin.

About Arendt

She now thought evil is never radical because it has no root. In no way does this limit evil, but on the contrary, it erases its limits and extends its reach. It is because it has no root that banal or thoughtless evil can spread over the entire surface of the earth. Radical evil may have been a “theory” to Kant — one, to be sure, he never developed — but never to Arendt.

... For her the reason Eichmann had to hang was not because he committed a “crime against nature,” though many, perhaps even the Israeli judges, may have believed that, and not implausibly. But to Arendt his crime was against human plurality — the essence of the uniqueness of every human being, including himself — which confirms Arendt’s previous assertion of a human nature knowable only to God, never to mortals. Eichmann was sentenced to death, not as punishment for what he had done (what possible punishment would be commensurate with his crime?), but because he failed to think what he was doing when he served as an officer in the Gestapo, or when after the war he escaped to Argentina, or when he was taken from there to Jerusalem to stand trial for his acts. Arendt’s judgment of Eichmann is that there is no place for such a man in the human world. He could not see that world from anyone else’s point of view, noticeably not of those Jews he admired and worked with. That is banal, and (this is the hardest part) the banality of the extreme evil for which as a human being, not a monster, he was responsible.

| Theses thoughts of Arendt made her famous for a larger crowd. This movie about Arendt focuses on the Eichmann trial. | Diese Gedanken von Arendt machten sie für ein größeres Publikum berühmt. Dieser Film über Arendt konzentriert sich auf den Eichmann-Prozess. | Estos pensamientos de Arendt la hicieron famosa para un público más amplio. Esta película sobre Arendt se centra en el juicio a Eichmann. |

What is to be noted here is that it is not Eichmann whom Arendt calls “outrageously stupid” — as the original title, Eichmann war von empӧrender Dummheit, implies — but the story. It is through her own reproductive imagination that Arendt can understand that attempting to communicate with Eichmann would be the same as talking “to a brick wall.”

If Christian belief had prevailed into the 20th century, according to Arendt, its fear of Hell would have prevented the horrors of totalitarian domination. But she also sees that Christian belief would have remained an obstacle to knowing ourselves and of what we are capable. Arendt distinguishes between having faith in a credo and true religious trust in the meaningfulness of creation.

What Hegel states about philosophy in general, that “the owl of Minerva spreads her wings only with the falling of the dusk,” holds only for a philosophy of history, that is, it is true of history and corresponds to the view of historians. Hegel of course was encouraged to take this view because he thought that philosophy had really begun in Greece with Plato and Aristotle, who wrote when the polis and the glory of Greek history were at their end. Today we know that Plato and Aristotle were the culmination rather than the beginning of Greek philosophic thought, which had begun its flight when Greece had reached or nearly reached its climax. What remains true, however, is that Plato as well as Aristotle became the beginning of the occidental philosophic tradition, and that this beginning, as distinguished from the beginning of Greek philosophic thought, occurred when Greek political life was indeed approaching its end.

When Marx made labor the most important activity of man, he was saying, in terms of the tradition, that not freedom but compulsion is what makes man human. When he added that nobody could be free who rules over others he was saying, again in terms of the tradition, what Hegel, in the famous master-servant dialectic, had only less forcefully said before him: that no one can be free, neither those enslaved by necessity nor those enslaved by the necessity to rule. In this Marx not only appeared to contradict himself, insofar as he promised freedom for all at the same moment he denied it to all, but to reverse the very meaning of freedom, based as it had been on the freedom from that compulsion we naturally and originally suffer under the human condition.

In Herodotus’ great definition (to which Marx’s statement conforms almost textually), a man is free who wants “neither to rule nor to be ruled.”

- I fully agree.

Freedom therefore was not one of the political “goods,” such as honor or justice or wealth or any other good, and it never was enumerated as belonging to man’s eudaimonia, his essential well-being or happiness. Freedom was the pre-political condition of political activities and therefore of all the goods that men can enjoy through their living together. As such, freedom was taken for granted and did not need to be defined. When he stated that the political life of a free citizen was characterized by logon echon, by being conducted in the manner of speech, Aristotle defined the essence of free men and their behavior, not the essence of freedom as a human good.

Plato still thought that these forms of government were plainly perversions, no true politeiai but born from some violent upheaval and depending on violence. The use of violence disqualifies all forms of government because, according to the older conception, violence begins wherever the polis, the political realm proper, ends.

The question whether Marx, who at the end of the tradition challenged its formidable unanimity about the proper relationship between philosophy and politics, was a philosopher in the traditional sense or even in any authentic sense, need not be decided. The two decisive statements that sum up abruptly and almost inarticulately his thought on the matter — “The philosophers have only interpreted the world…the point, however, is to change it,” and “You cannot supersede [aufheben in the Hegelian threefold sense of conserve, raise to a higher level, and abolish] philosophy without realizing it” — are so intimately phrased in Hegel’s terminology and thought along his lines that, taken by themselves, their explosive content notwithstanding, they can almost be regarded as an informal and natural continuation of Hegel’s philosophy.

Marx does not challenge philosophy, he challenges the alleged impracticality of philosophy. He challenges the philosophers’ resignation to do no more than find a place for themselves in the world, instead of changing the world and making it “philosophical.” And this is not only more than but also decisively different from Plato’s ideal of philosophers who should rule as kings, because it implies not the rule of philosophy over men but that men become philosophers. The consequence that Marx drew from Hegel’s philosophy of history (and Hegel’s entire philosophical work, including the Logik, has only this one topic: history) was that action, contrary to the philosophical tradition, was so far from being the opposite of thought that it was its true, namely real vehicle, and that politics, far from being infinitely beneath the dignity of philosophy, was the only activity that was inherently philosophical.

These considerations seemed necessary for an understanding of the last thinker who, still in the line of the great tradition, inquired into the nature of politics and asked the old questions about the different forms of government. Montesquieu, whose fame rests securely in the discovery of the three branches of government, the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary—that is, in the great discovery that power is not indivisible—was a political writer much rather than a systematic thinker. This enabled him to touch freely on and reformulate almost unintentionally the great problems of political thought as they had come down to him, without encumbering his new insights by making one working whole of them, and without disturbing the inner consistency of his thought with ulterior motives of presentation. His insights are in substance much more “revolutionary” and at the same time more enduringly positive than those of Rousseau, who is his only equal in the weight of sheer immediate impact on the 18th-century revolutions and of intellectual influence on the political philosophy of the 19th century. His lack of systematic concern, on the other hand, and the loose organization of his material have made it deplorably easy to neglect both the inner consistency of his widely scattered thoughts and the distinct unity of his approach to all political matters, which separates him only slightly less from his successors than from his predecessors.

Corresponding to his three chief forms of government, Montesquieu distinguishes three principles “which make a community act”: these are virtue in a republic, honor in a monarchy, and fear in a tyranny. These principles are not the same as psychological motives. They are rather the criteria according to which all public actions are judged and which articulate the whole of political life.

What determines both Plato’s and Aristotle’s notion of the essence of politics is the daily living together of many people within the walls of one limited space. What relates these many to each other are two experiences: equality and difference. The sense of equality, however, as it appeared with the foundation of the polis, was very different from our own belief in universal equality. First, it was not universal but pertained only to those who in actual fact were equals; excluded from it as a matter of course were the unfree, namely, slaves, women, and barbarians. Freedom and equality therefore in the beginning were corresponding notions and no conflict was felt to exist between them. Since equality did not extend to all men, it was not seen against the background of a common human fate, as is the equality of all men before death; nor was it measured against the overwhelming reality of a superhuman being, as is the equality before God.

We are told, for instance, that only Christian and God-fearing people can constitute a democracy, or that religion is the only force in the Western world with which to fight communism effectively, etc. I think that this reamalgamation of religion and politics is quite harmful, and even more harmful to religion than it is to politics. … The degradation of religion into an instrument of politics certainly endangers freedom of religion, and in this sense this freedom is indeed one of the latent issues.

Here the basic issue is freedom of movement, which is perhaps the most fundamental, certainly second to no other, of the freedoms we cherish. (One may remember in this context that the Greek formulae for the manumission of slaves enumerated the right to unrestricted movement among the four liberties which together constituted individual freedom—the others being status, personal inviolability, and professional freedom.) In a time when one cannot travel without a passport, freedom of movement is restricted or made a “privilege” if the government is not obliged to give a passport to each citizen who applies for it. The right to refuse applications should be restricted to cases in which freedom of movement is restricted anyhow, such as the cases of criminals or material witnesses or persons subject to arrest but free on bail.

Thucydides reports a famous saying by Pericles, in which the politically founded suspicion of culture is expressed in an indirect but nevertheless strikingly characteristic way. I am referring to the phrase, all but impossible to translate, philosophoumen aneu malakias kai philokaloumen met’euteleias. Here we can clearly hear that it is the polis, the political, which limits the love for wisdom and the love for beauty (both of which are understood, however—and that is what makes the phrase untranslatable—not as states but rather as activities); for it is euteleia, the accuracy that prevents excess, which is a political virtue, whereas malakia, as reported by Aristotle, was considered a barbaric vice of excess; the primary thing, however, which the Greeks believed elevated them above the barbarians was the polis, the political. In other words, by no means did the Greeks believe that it was their higher form of culture that distinguished them from the barbarians. Quite the contrary, it was the fact that the political limited the cultural.

| Very interesting thought, that for a civilization the political needs to limit the cultural. My impression is, that today the cultural (extremists) exacerbate the political, which in turn is nowhere near able to limit the cultural. What do you think? | Sehr interessanter Gedanke, dass für eine Zivilisation das Politische das Kulturelle begrenzen muss. Mein Eindruck ist, dass heute das Kulturelle (Extremisten) das Politische verschlimmert, das wiederum bei weitem nicht in der Lage ist, das Kulturelle zu begrenzen. Was meint Ihr? | Muy interesante la idea de que para que haya civilización es necesario que lo político limite lo cultural. Mi impresión es que hoy en día lo cultural (los extremistas) exacerba lo político, que a su vez no es capaz de limitar lo cultural. ¿Qué opina usted al respecto? |

You will recall that Kant’s political philosophy in the Critique of Practical Reason posits the legislative faculty of reason, and it assumes that the principle of legislation as it is determined by the “categorical imperative” rests on an agreement of rational judgment with itself—which is to say, in Kantian terms, that if I do not want to contradict myself, I must act only on those maxims that could, in principle, also be general laws. The principle of self-agreement is very old. One of its forms, which is analogous to Kant’s, can be already found in Socrates, whose central doctrine, in its Platonic formulation, reads as follows: “Since I am one, it is better for me to be in contradiction with the world than to be self-contradictory.” This proposition has formed the basis for Western conceptions of ethics and logic, with their emphases on conscience and the law of noncontradiction respectively. Under the heading “maxims of Common Sense” in the Critique of Judgment, Kant now adds to the principle of agreement with oneself the principle of an “enlarged way of thinking,” which submits that I can “think from the standpoint of everyone else.” The agreement with oneself is thus joined by a potential agreement with others. The power of judgment rests on this enlarged way of thinking, and judging thereupon derives its proper power of legitimacy.

It is an odd fact which, of course, has often been noticed that Jefferson, when he drafted the Declaration of Independence, changed the current formula in which the inalienable rights were enumerated from “life, liberty and property” to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” It is even stranger that in the debates which preceded the adoption of Jefferson’s draft this alteration was not discussed; and this curious lack of attention to a phraseology, which in the course of the following centuries has contributed to a specifically American ideology more than any other word or notion, stands almost as much in need of explanation as the phrase itself.

| I'd prefer "life, liberty and property" as happiness seems as a foolish goal to me. | Ich würde "Leben, Freiheit und Eigentum" vorziehen, denn Glück scheint mir ein unsinniges Ziel zu sein. | Yo preferiría "vida, libertad y propiedad", ya que la felicidad me parece un objetivo absurdo. |

On freedom

Which, then, was the background of experience from which the term “public freedom” was coined? Who were the men who, without even knowing it (for “the very notion of a violent revolution had no place in [their] mind; it was not discussed because it was not conceived,” as Tocqueville pointed out), were in fact bent upon changing the old order of a whole civilization? The 18th century, as I mentioned before, called these men hommes de lettres, and one of their outstanding characteristics was they had withdrawn voluntarily from society, first from the society of the royal court and the life of a courtier, and later from the society of the salons. They educated themselves and cultivated their minds in a freely chosen seclusion, putting themselves at a calculated distance from the social as well as the political, from which they were excluded in any case, in order to look upon both in perspective. Living under the rule of an enlightened absolutism where life at the king’s court, with its endless intrigues and the omnipresence of gossip, was supposed to offer full compensation for a share in the world of public affairs, their personal distinction lay in their refusal to exchange social consideration for political significance, opting rather for the secluded obscurity of private studies, reflections, and dreams. We know this atmosphere from the writings of the French moralistes, and we still are fascinated by the considered and deliberate contempt for society in its initial stages, which was the source even of Montaigne’s wisdom, the depth of Pascal’s thought, and which left its traces upon many pages of Montesquieu’s work.

Even this view of things, alienating as it perhaps may be, is still entirely in accordance with traditional political thought. Montesquieu, for example, believes the sign of a free nation is people making any use at all of their reason (raisonner), and that, no matter whether they do this well or badly, the fact that they are thinking is enough to bring about freedom. Therefore it is characteristic of a despotic regime that the principle of domination is put in jeopardy as soon as people begin to reason —even if they then try to mount a theoretical justification of tyranny.

This has nothing to do with truth, or any other by-product of thinking; it is the sheer activity of reasoning itself from which freedom arises. Reasoning creates a space between men in which freedom is real. Now, again according to Montesquieu, the curious thing about this freedom that arises from the activity of reasoning is that it provides protection against the results of Reason (raisonnement), for where freedom, or rather the space for freedom between people engendered by reasoning, is destroyed, as is the case in all tyrannical forms of state, the results of reasoning can only be pernicious. Which is to say, where freedom has stopped being a worldly reality, freedom as an individual’s subjective capacity can only lead to ruin, as modern dictators understand only too well. They cannot permit freedom of thought —as the events following Stalin’s death have shown us—even if they want to.

- Great paragraph on freedom.

To illustrate how difficult it is within the conceptual structure of our philosophical tradition to formulate a concept of freedom that conforms with political experience, I want to look at two modern thinkers who, in terms of both political philosophy and theory, are perhaps the greatest and most profound— namely, Montesquieu and Kant.

Montesquieu is so aware of the inadequacies of the philosophical tradition in these matters that he expressly distinguishes between philosophical and political freedom. The difference is that philosophy demands no more of freedom than the exercise of the will (l’exercice de la volonté), independent of circumstances in the world and of attainment of the goals the will sets for itself. Political freedom, by contrast, is the security (la liberté politique consiste dans la sûreté) that does not exist always and everywhere, but only in political communities governed by laws.

Without security there is no political freedom, for freedom means “being able to do what one ought to will” (la liberté ne peut consister qu’à pouvoir faire ce que l’on doit vouloir). As obvious as these sentences make Montesquieu’s propensity to juxtapose the philosophical freedom of a willing self with being free politically, a worldly, tangible reality, his dependency on the philosophical tradition of free will is no less evident. For Montesquieu’s definitions sound as if political freedom is nothing but an extension of philosophical freedom, namely, the freedom that is indispensable for the realization of the freedom of an I - will. If we want to understand Montesquieu’s real intentions, however, we must take the trouble to read his sentences so that the emphasis does not fall on the I-can—the notion that one must be able to do what one wants or should want—but on the deed. It should be added that actions and deeds are viewed here as considerably more significant than the quasi-automatic fulfillment of the will. Freedom itself is enacted in action, and the security that guarantees the ability to perform them is provided by others. This freedom does not reside in an I-will, which the I-can may either comply with or contradict without bringing man’s philosophical freedom into question; political freedom begins only in action, so that not-being-able-to-act and not-being-free amount to one and the same thing, even if philosophy’s free will continues to exist intact. In other words, political freedom is not “inner freedom”; it cannot hide inside a person. It is dependent on a free people to grant it the space in which actions can appear, be seen, and be effective. The power of the self-assertion of the will to compel others has nothing whatever to do with this political freedom.

In Kant, the only one among the great philosophers for whom the question “What should I do?” held the same dignity as the specifically philosophical questions: “What can I know? What may I hope?” The strength of the antipolitical tradition in philosophy does not show itself in insufficient formulations as it does in Montesquieu, but in the remarkable fact that in Kant there are two very different political philosophies: the one that is generally accepted as such in the Critique of Practical Reason, and the other in the Critique of Judgment. The literature on Kant rarely mentions that the first part of the Critique of Judgment is actually a philosophy of politics; I believe one can, however, demonstrate that in all his political writings the theme of judgment carried more weight for Kant than did that of practical reason. Freedom appears in the Critique of Judgment as a predicate of the imagination, not of the will, and the imagination is most intimately related to that “enlarged mentality,” which is the political way of thinking par excellence, because through it we have the possibility “to think in the position of everyone else.” Only in this context does it become philosophically clear why Kant was able to say emphatically: “The external force that wrenches away people’s public freedom to communicate their thoughts also takes from them their freedom to think.” Here, being unfree retaliates against the “inner” ability to be free and destroys it. Even freedom of thought, as Kant puts it, the inner “conversation with oneself” depends, if it is to issue in thoughts, on the presence of others and thus on the opportunity to “advance our thoughts in public to see whether they agree with the understanding of others.” But this concept of freedom as entirely independent of free will has played hardly any role in the reception of Kant’s philosophy. And even in Kant’s philosophy itself it is overshadowed by that of “practical reason” which ascribes to the will, for good or evil, all power in human affairs, while action itself, as you will remember, no longer falls within the sphere of human power and freedom, but is subordinate to necessity and subject to the law of causality. To be free only as long as one can will, means only as long as the I - will is not opposed by an inner I - cannot, which in turn means that one becomes unfree as soon as one begins to act. Kant had hardly any doubt about these two fundamental propositions in the narrower sense of his practical-political philosophy.

European man has always known that freedom as a mode of being and a worldly reality can be destroyed, and that only seldom in history has it unfolded its full virtuosity. Now that we are acquainted with totalitarianism we must also suspect that not only being free but also the sheer gift of freedom, which was not produced by man but given to him, may be destroyed, too. This knowledge or suspicion weighs more heavily upon us now than ever before, for today, more depends on human freedom than before—on man’s ability to tip scales heavily weighted toward disaster, which always happens automatically and therefore always appears irresistible. This time, no less than the continued existence of men on earth may depend upon man’s gift of performing “miracles,” that is, bringing about the infinitely improbable and establishing it as a worldly reality.

About Heidegger (with whom Arendt had an affair)

For it is not Heidegger’s philosophy, whose existence we can rightfully question (as Jean Beaufret has done), but Heidegger’s thinking that has had such a decisive influence on the spiritual physiognomy of this century. This thinking has a digging quality peculiar to itself, which, should we wish to put it in linguistic form, lies in the transitive use of the verb “to think.” Heidegger never thinks “about” something; he thinks something. In this entirely uncontemplative activity, he penetrates to the depths, but not to discover, let alone bring to light, some ultimate, secure foundation which as yet had been undiscovered. Rather, he persistently remains there, underground, in order to lay down pathways and fix “trail marks” (a collection of texts from the years 1929 to 1962 had this title, Wegmarken). This thinking may set tasks for itself; it may deal with “problems”; it naturally, indeed always, has something specific with which it is particularly occupied, or, more precisely, by which it is specifically aroused; but one cannot say that it has a goal.

It is unceasingly active, and even the laying down of paths itself is conducive to opening up a new dimension of thought, rather than reaching a goal sighted beforehand and then aimed at. The pathways may safely be called Holzwege, wood-paths (after the title of a collection of essays from the years 1935 to 1946), which, precisely because they lead nowhere outside the wood and “abruptly leave off in the untrodden,” are incomparably more agreeable to him who loves the wood and feels at home in it than the streets with their carefully laid out problems where the investigators of philosophical specializations and historians of ideas scurry. The metaphor of “wood-paths” hits upon something essential—not, as one may at first think, that someone has gotten onto a dead-end trail, but rather that someone, like the lumberjack whose occupation lies in the woods, treads paths that he himself has beaten; and clearing the path belongs no less to his line of work than the felling of trees.

We are so accustomed to the old opposition of reason versus passion, spirit versus life, that the idea of a passionate thinking, in which thinking and being alive become one, takes us somewhat aback. Heidegger himself once expressed this unification —in a well-documented anecdote—in a single sentence, when at the beginning of a course on Aristotle he said, in place of the usual biographical introduction, “Aristotle was born, worked, and died.” That something like Heidegger’s passionate thinking exists is indeed, as we can recognize afterward, a condition of the possibility of there being any philosophy at all. But it is more than questionable, especially in our century, whether we would ever have discovered this apart from Heidegger’s example of a thinking existence. This passionate thinking, which rises out of the simple fact of being-born-into-the-world and then “thinks recallingly and responsively the meaning that reigns in everything that is” (Gelassenheit, 1959, p.15), can no more have a final goal—cognition or knowledge—than can life itself. The end of life is death, but man does not live for death’s sake, but because he is a living being; and he does not think for the sake of any result whatever, but because he is a “thinking, that is, a sentient being” (ibid.).

For Martin Heidegger

On his 80th birthday, his contemporaries honor the master, the teacher, and— for some surely—the friend. We pause to try to give an account of what this life means for us, for the world, and for our time, this life that in its gathered fullness only now appears as wholly present in the present, which is, I suppose, the blessing of old age. Each individual may have a different answer to the question at hand; may each answer do justice, at least to some degree, to the passion of the fulfillment of this life to which the work bears witness.

To me it seems that this life and work have taught us what thinking is, and that the writings will remain exemplary of that, and of the courage to venture into the immensity of the untrodden, to open oneself entirely to what is as yet unthought, a courage possessed only by him who turns himself entirely to thinking and its tremendous depth.

May those who follow us, if they recall our century and its people and try to keep faith with us, not forget the devastating sandstorms that swept us all up, each in his own way, and in which such a man as this and his work were still possible.

We are in an unprecedented era but, as a matter of fact, almost all events in history, when they occurred, were novel. In Christianity, for example, what in God’s name, in that day and era, indicated the arrival of Jesus of Nazareth? What indicated the arrival of Paul, which for Western history is much more important? To look to the past in order to find analogies by which to solve our present problems, is, in my opinion, a mythological error. If you cannot read these great books with love and pure motives and just because you are fond of the life of the spirit—the life of the mind—it won’t do you any good and it won’t do students any good.

Questions and answers

KRISTOL: One teacher can produce six serious thinkers, if he’s lucky, in a lifetime. That’s a lot. Five teachers can produce thirty. One has to assume that this is for the good. And what a foundation can do—or what something like the National Endowment for the Humanities can do—is try to find these key people. There aren’t that many but there are a few dozen in the United States who are genuine believers and authentically superb teachers because they are genuine believers.

ARENDT: I think a problem that really needs to be worked on, and where the foundation may be of help, is that really good teachers are not thought of highly by the academic society. This business of “publish or perish” has been a catastrophe. People write things which should never have been written and which should never be printed. Nobody’s interested. But for them to keep their jobs and get the proper promotion, they’ve got to do it. It demeans the whole of intellectual life. I used to adhere to the principle that a graduate student on a certain level should be independent from me to the extent that he could also, apart from me, choose and establish his own bibliography. This is absolutely impossible today because there is such an amount of sheer nonsense on the market that you cannot ask the student to review it. He will spend years in the library until he finds the few really important books in the field.

... Reason itself, the thinking ability which we have, has a need to actualize itself. The philosophers and the metaphysicians have monopolized this capability. This has led to very great things. It also has led to rather unpleasant things—we have forgotten that every human being has a need to think, not to think abstractly, not to answer the ultimate questions of God, immortality, and freedom, nothing but to think while he is living. And he does so constantly. Everybody who tells a story of what happened to him half an hour ago on the street has got to put this story into shape. And this putting the story into shape is a form of thought.

So in this respect it may even be nice that we lost the monopoly of what Kant once very ironically called the “professional thinkers.” We can start worrying about what thinking means for the activity of acting. Now I will admit one thing. I will admit that I am, of course, primarily interested in understanding. This is absolutely true. And I will admit that there are other people who are primarily interested in doing something. I am not. I can very well live without doing anything. But I cannot live without at least trying to understand whatever happens.

... Property is another question. Property is indeed very important, but in a different sense than the one in which you think about it. What we should encourage everywhere is property—of course, not the property of the means of production, but private property strictly speaking. And, believe me, this property is very much in danger, either by inflation, which is only another way of expropriating the people, or by exorbitant taxes, which is also a way of expropriation. These are the sweeter ways to expropriate—instead of pillage and killing. These processes of expropriation you have everywhere. To make a decent amount of property available to every human being—not to expropriate, but to spread it out—then you will have some possibilities for freedom even under the rather inhuman conditions of modern production.

MACPHERSON: Really, two of the statements Miss Arendt has made this morning about power seem to me outrageous. One was that Marx didn’t understand power. And the other was that power is not in the bureaucracy. It seems to me that one can hold that Marx didn’t understand power only if you define power in some very peculiar way. And it strikes me that this is part of the pattern of Miss Arendt’s thought. She defines a lot of key words in ways unique to herself: you know, social versus political (a rather special meaning to the word “social”), force versus violence (a quite special meaning to the word “force”)….

ARENDT: No, power versus violence, I am sorry.

MACPHERSON: Power and violence, sorry. Action (a unique definition of “action”). This intellectual practice—and it’s a very enlivening practice, because it starts off, or should start off, all kinds of controversy—is still rather curious: it takes a word that has perhaps more than one meaning in the ordinary understanding and gives it a very special meaning and then proceeds from there to reach striking, paradoxical conclusions.

Well, look, Marx didn’t understand power, you say. What he understood, surely, was that power is in any society wielded by the people who control access to the means of production, the means of life, the means of labor. And that, in his terminology, was a class. Would Miss Arendt agree that the only reason a bureaucracy has what power it has—and I wouldn’t agree with her that it has anything like the power she attributes to it—because and only insofar as, and only in those countries where it has become a class in Marx’s sense, that is, of the people who control access to the means of production?

ARENDT: I would not agree with this. What you consider my idiosyncratic use of words—I think there is a little more to it, of course. We all grow up and inherit a certain vocabulary. We then have got to examine this vocabulary. And this not just by finding out how this word is usually used, which then results in a certain number of uses. These uses are then, so to speak, legitimate. In my opinion a word has a much stronger relation to what it denotes or to what it is than the way it is being used between you and me. That is, you look only to the communicative value of the word. I look to the disclosing quality. And this disclosing quality has, of course, always an historical background.

MACPHERSON: I look at the disclosing quality, too, and that’s why I say that such words as Marx’s use of class, power, and so on were disclosing concepts.

ARENDT: I didn’t say the same about class. You see what I mean is, of course, the so-called superstructure. What Marx means by power is actually the power of a trend or development. This, he then believes, materializes—despite it’s being utterly immaterial—in the superstructure, which is the government. Thus the laws of the government as superstructure are nothing but mirrors of the trends in society. The question of rule Marx did not understand and to a large extent that is in his favor because he did not believe that anybody wants power just for power’s sake. This does not exist in Marx. Power in the naked sense that one person wants to rule another, and that we need laws in order to prevent that, this Marx didn’t understand.

You know, somehow Marx still believed that if you leave men alone— society corrupts man—and change society man will reappear. He will reappear—God protect us from it: this optimism, runs throughout history. You know, Lenin once said he doesn’t understand why criminal law should exist, because once we have changed circumstances everybody will prevent everybody else from committing a crime, as a matter of course, just as every man will hurry up to aid a woman who is in distress. I also thought this example of Lenin so very nineteenth-century, you know. All this we do not believe any longer.

ARENDT: Well, of course, I did something like Montesquieu did with the English Constitution in that I construed out of the American Constitution a certain ideal type. I tried to back it up a little better than Montesquieu with historical fact, for the simple reason that I do not belong to the aristocracy and therefore do not enjoy this blessed laziness which is one of the main characteristics of Montesquieu’s writings. Now whether this is permissible is another question, which would lead us too far here. Actually we all do that. We all somehow make what Max Weber called an “ideal type.” That is, we think a certain set of historical facts, and speeches, and so forth, through, until it becomes some type of consistent rule. This is especially difficult with Montesquieu because of his laziness; it is much easier with the Founding Fathers because they were extraordinarily hard workers; they give you everything you want.

You see, I only half went back to Greek and Roman antiquity because I like it so much —I like Greek antiquity far more than Roman antiquity. I went back nevertheless because I knew that I simply wanted to read the same books these people had read. They read these books—as they would have said—to find a model for a new political realm they wanted to bring about, and which they called a republic. … The model of man of this republic was to a certain extent the citizen of the Athenian polis. After all, we still have words from then, and they echo through the centuries. On the other hand, the model was the res publica, the public thing, of the Romans. The influence of the Romans was stronger in its immediacy on the minds of these men. You know Montesquieu didn’t only write L’Esprit des Lois but also wrote about la grandeur and la misère of Rome. These readers were all absolutely fascinated. … They taught themselves a new science, and they called it a new science. Tocqueville was the last who still talked about that. He says for this modern age we need a new science. He meant a new science of politics, not the nuova scienza of the previous generations, of Vico. And that is what I actually have in mind. I don’t believe something very tangible comes out of anything which people like me are doing, but what I am after is to think about these things, not just in the realm of antiquity, but because I feel the same need for antiquity that the great revolutionaries of the 18th century felt.

MORGENTHAU: What are you? Are you a conservative? Are you a liberal? Where is your position within the contemporary possibilities?

ARENDT: I don’t know. I really don’t know and I’ve never known. And I suppose I never had any such position. You know the left think I am conservative, and the conservatives sometimes think I am left, or I am a maverick or God knows what. And I must say I couldn’t care less. I don’t think that the real questions of this century will get any kind of illumination by this kind of thing.

I don’t belong to any group. You know the only group I ever belonged to were the Zionists. And this was from 1933 to 1943. And after that I broke. This was only because of Hitler, of course. The only possibility was to fight back as a Jew and not as a human being—which I thought was a great mistake, because if you are attacked as a Jew you have got to fight back as a Jew, you cannot say “excuse me, I am not a Jew; I am a human being.” This is silly. And I was surrounded by this kind of silliness. There was no other possibility, so I went into Jewish politics—not really politics—I went into social work and was somehow also connected with politics. I never was a socialist. I never was a communist. I come from a socialist background. My parents were socialists. But I myself, never. I never wanted anything of that kind. So I cannot answer the question.

I never was a liberal. When I said what I was not, I forgot to mention that. I never believed in liberalism. When I came to this country I wrote in my very halting English a Kafka article, and they had it “Englished” for the Partisan Review. And when I came to talk to them about the Englishing I read the article and there of all things the word “progress” appeared. I said: “What do you mean by this, I never used that word,” and so on. And then one of the editors went to the other in another room, and left me there, and I overheard him say, in a tone of despair, “She doesn’t even believe in progress.”

- I can very much feel that rejection of being assigned a political label.

So—this is how it can be, but don’t forget that: there is no religion without God. And that is a whole dimension of human life which is not political. It is neither private nor public. It is really beyond. And it would be sheer foolishness to claim, no matter which denomination we are dealing with, that this dimension can still prescribe—that we can still derive from this dimension a code of conduct, like the Ten Commandments. This I doubt, not because I doubt the Ten Commandments —on the contrary I think they are really pretty good!—but because people do not believe anymore. And you know, preaching won’t help. The most effective sermons were always about hellfire. And to forget that, in this very nice idealism of the Christian churches which are now in crisis, is too easy. Remember not to make life too easy for yourself!

ERRERA: Throughout history, what has ensured the survival of the Jewish people has been, mainly, a religious kind of bond. We are living in a period when religions as a whole are going through a crisis, where people are trying to loosen the shackles of religion. In these conditions, what, in the current period, comprises the unity of the Jewish people throughout the world?

ARENDT: I think you are slightly wrong with this thesis. When you say religion, you think, of course, of the Christian religion, which is a creed and a faith. This is not at all true of Judaism, which is a national religion where nation and religion coincide. You know that Jews, for example, don’t recognize baptism; for them it is as though it didn’t happen. That is, a Jew never ceases to be a Jew according to Jewish law. So long as somebody is born from a Jewish mother—la recherche de la paternité est interdite—he is a Jew. Thus the notion of what religion is, is altogether different, more a way of life than a religion in the particular, specific sense of Christianity. I remember, for instance, I had Jewish instruction, religious instruction, and when I was about 14 years old, of course I wanted to rebel and say something shocking to our teacher, so I got up and said, “I don’t believe in God.” Whereupon he said, “Who asked you?”

😂

The notion that private rights are sacrosanct is Roman in origin. The Greeks distinguished between the idion and the koinon, between what is one’s own and what is held in common. It is interesting that the former term has become in every language, including the Greek, the root for the word idiocy. The idiot is one who lives only in his own household and is concerned only with his own life and its necessities. The truly free state, then—one that respects not only certain liberties but is genuinely free—is a state in which no one is, in this sense, an idiot; that is, a state in which everyone takes part in one way or another in what is common.

| This was no easy read, but I enjoyed following Arendt's thoughts. An exceptionally bright person with the courage to make inconvenient statements. I wished we have more of her personality today. | Dies war keine leichte Lektüre, aber ich habe es genossen, Arendts Gedanken zu folgen. Eine außergewöhnlich kluge Person mit dem Mut, unbequeme Aussagen zu machen. Ich wünschte, wir hätten heute mehr von ihrer Persönlichkeit. | No fue una lectura fácil, pero disfruté siguiendo los pensamientos de Arendt. Una persona excepcionalmente brillante con el valor de hacer declaraciones inconvenientes. Ojalá tuviéramos más de su personalidad hoy en día. |

Have a great day,

zuerich

!MEME

Credit: fjworld

Earn Crypto for your Memes @ HiveMe.me!