Lying for money (book by Dan Davies)

| Dear Hiveans | Liebe Hiver | Queridos Hiveanos |

|---|---|---|

| Today I'd like to share my favourite excerpts from the book "Lying for money" (goodreads) by Dan Davies, who was a regulatory economist at the Bank of England and analyst for investment banks. "His career has seen him tackle all manner of financial crookedness, including the LIBOR and FX scandals, the collapse of Anglo Irish Bank, and the Swiss Nazi gold scandal." (Davies_website) | Heute meine Lieblingsauszüge aus dem Buch "Lying for money" von Dan Davies, der als Regulierungsökonom bei der Bank of England und als Analyst für Investmentbanken tätig war. "In seiner Laufbahn hat er sich mit allen Arten von Finanzkriminalität auseinandergesetzt, darunter die LIBOR- und Devisenskandale, der Zusammenbruch der Anglo Irish Bank und der Schweizer Nazi-Goldskandal." (Davies_website) | Hoy me gustaría compartir mis extractos favoritos del libro "Mentir por dinero", de Dan Davies, que fue economista regulador en el Banco de Inglaterra y analista de bancos de inversión. "Su carrera le ha llevado a enfrentarse a todo tipo de corruptelas financieras, incluidos los escándalos del LIBOR y las divisas, la quiebra del Anglo Irish Bank y el escándalo del oro nazi suizo". (Davies_website) |

We might call this the ‘Canadian Paradox’. There are different kinds of dishonesty in the world. The most profitable kind is commercial fraud, and commercial fraud is parasitical on the overall health of the business sector on which it preys. It is much more difficult to be a fraudster in a society in which people only do business with relatives or where commerce is based on family networks going back for centuries. It is much easier to carry out a securities fraud in a market where dishonesty is the rare exception rather than the everyday rule.

The existence of the Canadian Paradox suggests that there is a specifically economic dimension to a certain kind of crime of dishonesty. Trust – particularly between complete strangers, with no interactions beside relatively anonymous market transactions – is the basis of the modern industrial economy. And the story of the development of the modern economy is in large part the story of the invention and improvement of technologies and institutions for managing that trust. In other words, many things about the way the business world is organised make a lot more sense when you realise that they exist because of the constant drive for countries to become less like Greece and more like Canada.

| That's interesting. And I am curious in how Bitcoin will change the importance of trust - as it aims to be trustless (more). | Das ist sehr interessant. Und ich bin gespannt, wie Bitcoin die Bedeutung von Vertrauen verändern wird - da es darauf abzielt, trustless zu sein (mehr). | Es interesante. Y tengo curiosidad por saber cómo Bitcoin cambiará la importancia de la confianza, ya que su objetivo es no generar confianza (más). |

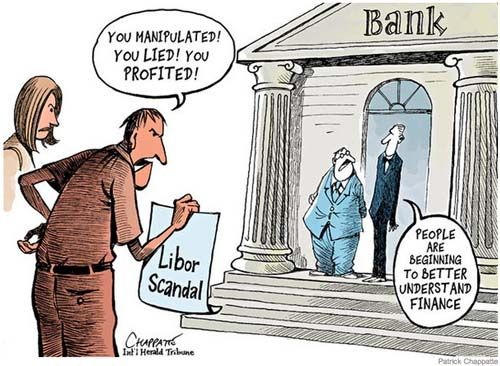

The LIBOR Scandal

With the perspective of a few years’ hindsight, the system was always a shoddy piece of work. Some not-very-well-paid clerks from the British Bankers’ Association called up a few dozen banks and asked ‘If you were to borrow, say, a million dollars in [a given currency] for a 30 day deposit, what would you expect to pay?’. They would throw away the highest and lowest outliers and calculate the average of the rest, which would be recorded as ‘30 day LIBOR’ for that currency. The process would be repeated for three-month loans, six-month loans and any other periods of interest, and the rates would be published. You would then have a little table recording the state of the market on that day – you could decide which currency you wanted to borrow in and how long you wanted the use of the money, and the LIBOR panel would give you a good sense of what high-quality banks were paying to do the same.

Compared to the amount of time and effort that goes into the systems for nearly everything else banks do, not very much trouble was taken over this process. Other markets rose and fell, stock exchanges mutated and were taken over by super-fast robots, but the LIBOR rate for the day was still determined by a process that could only slightly unfairly be termed ‘a quick ring-around’. Nobody noticed until it was too late that hundreds of trillions of dollars of the world economy rested on a number compiled by the few dozen people in the world with the greatest incentive to fiddle it.

When analysed properly, there isn’t much that is truly difficult about the proverbial ‘complex fraud trial’. The underlying crime is often surprisingly crude; someone did something dishonest and enriched themselves at the expense of others. What makes white-collar trials so arduous for jurors is really their length, and the amount of detail which needs to be brought for a successful conviction. Such trials are not long and detailed because there is anything difficult to understand. They are long and difficult because so many liars are involved. And when a case has a lot of liars, it takes time and evidence to establish that they are lying.

The way we might describe this is to say that fraud is an equilibrium quantity. We can’t check up on everything, and we can’t check up on nothing, so one of the key decisions that an economy has to make is how much effort to spend on checking. This choice will determine the amount of fraud. And since checking costs money and trust is really productive, the optimal level of fraud is unlikely to be zero.

Another way of stealing money through commercial fraud is to abuse people’s trust in the ways by which ownership and value are verified. Again, the fraudster exploits the fact that a world in which every single document was checked, every claim of ownership verified and every certificate of quality audited, would be a world in which a huge proportion of the business world’s time and effort was wasted by checking up on each other. The only practical way to do many types of business is to trust that, for the most part, documents are what they appear to be, and that they prove what they claim to prove. Abusing this trust by creating false documents to verify false claims is counterfeiting.

The founder of Stratton Oakmont called his autobiography The Wolf of Wall Street, presumably because ‘Tales of a Parasite’ would not have been as good for sales. It is a memorably emetic book, full of simpering, sniggering self-aggrandisment and insincere contrition, and it starts with four consecutive chapters about a time he passed out on his front lawn from taking drugs. But it does contain one paragraph which partly redeems the rest of the book and which summarises the business model of ‘boiler room’ stockbroking:

"And what secret formula had Stratton discovered that allowed all these obscenely young kids to make such obscene amounts of money? For the most part it was based on two simple truths; first, that a majority of the richest 1% of Americans are closet degenerate gamblers, who can’t withstand the temptation to keep rolling the dice again and again, even if they know the dice are loaded against them; and second, that contrary to previous assumptions, young men and women who possess the collective social graces of a herd of sex-crazed water buffalo and have an intelligence quotient in the range of Forrest Gump on three hits of acid, can be taught to sound like Wall Street wizards, as long as you write every last word down for them and then keep drilling it into their heads again and again – every day, twice a day – for a year straight."

Auditors, analysts and other disappointments

All of these frauds should have been prevented by the auditors, whose job it specifically is to review every set of accounts as a neutral outside party and certify that they are a true and fair view of the business. But they didn’t. Why not? The answer is simple; some auditors are crooks, and some are easily fooled by crooks. And whatever reforms are made to the accounting standards and to the rules governing the profession, the same problems have cropped up again and again. As always, when something keeps happening in different times and places, it’s likely to be an equilibrium phenomenon linked to the deep underlying economic structure.

First, there is the problem that the vast majority of auditors are both honest and competent. This is a good thing, of course, but the bad thing about it is that it means that most people have never met a crooked or incompetent auditor and therefore have no real understanding that such people exist. In order to find a really bad guy at a Big Four accountancy firm, you have to be quite unlucky (or quite lucky if that was what you were looking for). But as a crooked manager of a company, churning around your auditors until you find a bad ’un is exactly what you do, and when you find one, you hang on to them. This means that the bad auditors are gravitationally drawn into auditing the bad companies, while the majority of the profession has an unrepresentative view of how likely that could be.

Second, there is the problem that even if an auditor is both honest and competent, he has to have a spine or he might as well not be. Fraudsters can be both persistent and overbearing and not all the people who went into accountancy firms out of university did so because they were commanding alpha-type personalities. Added to this, fraudsters are really keen on going over auditors’ heads and complaining to their bosses at the accounting firm, claiming that the auditor is being unhelpful and bureaucratic, not allowing the CEO to use his legitimate judgement in presenting the results of his own business. Partly because auditors are often awful stick-in-the-muds and ass-coverers, and partly because audit is a surprisingly competitive and unprofitable business which is typically used as a loss-leader to sell more remunerative consulting and IT work, you can’t at all assume that the auditor’s boss will support his employee, even though the employee is the one who is placing his signature (and the reputation of the whole practice) on the set of accounts. As with several other patterns of behaviour that tend to generate frauds, the dynamic by which a difficult audit partner gets overruled or removed happens so often and reproduces itself so exactly that it’s got to reflect a fairly deep and ubiquitous incentive problem which will be very difficult to remove.

| This makes me think of Enron and its external auditor which was Arthur Andersen (wiki), and of the German shooting star wirecard (wiki) whose auditor was Ernst & Young - who merged with Arthur Andersen in 2002. Fraudsters stay fraudsters. | Das erinnert mich an Enron und seinen externen Wirtschaftsprüfer Arthur Andersen (wiki), und an den deutschen Shootingstar Wirecard (wiki), dessen Wirtschaftsprüfer Ernst & Young war - der 2002 mit Arthur Andersen fusionierte. Betrüger bleiben Betrüger. Hier noch ein Schmankerl vom Schwätzer Mr. Dax: https://finanzmarktwelt.de/dirk-mueller-mr-dax-ueber-wirecard-humor-am-mittwoch-204492/ | Esto me hace pensar en Enron y su auditor externo que era Arthur Andersen (wiki), y en la estrella fugaz alemana wirecard (wiki) cuyo auditor era Ernst & Young - que se fusionó con Arthur Andersen en 2002. Eso en cuanto a que los defraudadores se quedan en defraudadores. |

The fraud triangle model is the equivalent of the classic murder triangle beloved of detective novelists. Rather than means, motive and opportunity, it suggests that a fraud happens when the following conditions are simultaneously met:

- Need. Bankers commit acts of dishonesty for the same reason that heroin addicts do; they have been put in a position where they need to come up with larger sums of money than they can generate by honest means. This side of the triangle is agnostic as to the reason for the need; simple greed, institutional pressure, fear of admitting failure or whatever underlying cause, the first component of a fraud is someone who needs the money.

- Opportunity. An opportunity to commit fraud is a weakness in a control and checking system – either one which exists because of the way in which the intrinsic variety of the system has been reduced to make it manageable, or one that the fraudster himself has created by exploiting a position of control.

- Rationalisation. White-collar crime is committed by people who have been trusted with something, and there are psychological barriers to breaking a trust. Usually, before an opportunity to commit fraud is exploited by a person with a need, the fraudster will have to come up with a way of overcoming these barriers. This is a ‘rationalisation’ – a way of redescribing the crime so as to make it less emotionally repellent.

There are some things that you can say about the likely properties of a fraud though. First, that it will grow over time, and that it will probably grow quickly, because most frauds have the snowball property. And second, that if it is an entrepreneurial fraud, it will be something which bypasses all of the processes and controls that have been set up to prevent it so far. That’s the basis of my proposal for a Golden Rule: Anything which is growing unusually quickly needs to be checked out, and it needs to be checked out in a way that it hasn’t been checked before. Nearly all of the frauds in this book could have been stopped a lot earlier if people had been a bit more cynical about growth. […]

We always face the same dilemma: do you want to reduce fraud to a minimum, or do you want to be rich? The decision about what market crimes to create is not so different from the decision about how strictly to enforce laws against unambiguous crimes of dishonesty. The cost of eliminating dishonesty is much more to do with the amount of legitimate business that never gets done. The cost of dishonesty itself is inseparable from the extent to which bad actors drive out good. The trade-off that we need to make at the level of society is between these two quantities. Perhaps the best that we can do is to accept that fraud is an inevitable part of society, bring up our children to be honest, and adopt a sceptical – but not too cynical – attitude to things that seem too good to be true.

| We, in the crypto realm, had our own examples of too much growth in too short a time, such as Bitconnect or FTX. Now that the SEC tries to "regulate" this realm, it'll be interesting to watch if similar things will happen again. | Wir in der Kryptowelt hatten unsere eigenen Beispiele für zu viel Wachstum in zu kurzer Zeit, wie Bitconnect oder FTX. Nun, da das SEC versucht, diesen Bereich zu "regulieren", wird es interessant sein zu beobachten, ob ähnliche Dinge wieder passieren werden. | Nosotros, en el ámbito de las criptomonedas, hemos tenido nuestros propios ejemplos de crecimiento excesivo en muy poco tiempo, como Bitconnect o FTX. Ahora que la SEC intenta "regular" este ámbito, será interesante ver si vuelven a ocurrir cosas similares. |

Have a great day,

zuerich

!MEME

Credit: drpanayiothss

Earn Crypto for your Memes @ HiveMe.me!

If these details was fetch from the book, then it's a book I need to get. Indeed there are fraudsters in the economy system. I imagine the loan organisation that calculates ones interest depending on the amount or period to be repaid and just sit back and expect their money to work for them stealing much for a man's sweat.

It's indeed a world of people lying for money

This is really worth reading. Hopefully, I can get an audiobook so I can listen to it while working.

Finance is really a mathematical game that the government and banks have been playing for years. However crypto is now making it possible for us to be able to escape their fraud and become the printers and keepers of our assets.

Dear @zuerich !

Many East Asians speculate that Europe's economy will plummet further after the war in Ukraine!

It is argued that Asian economies outperform European economies!

Yes, I expect that, too. Europe is in decline, demographically, economically, morally. Some

Asian economies could outperform Europe by far, perhaps India, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines?

Opinions prevail that China, India and Japan can clearly outperform Europe's economies!

Today I was able to soak up the knowledge you describe from the book "Lying for money" about fraud, it is compared to the Canadian paradox. We can't control everything, we can't control anything. A key decision an economy must make is controls. These determine the amount of fraud. Another way to steal money is through commercial fraud, abusing people's trust. Also by pretending that documents are what they appear to be and that they prove what they say. Abusing trust when the documents are false, then it is forgery. You make a golden rule proposition: Anything that grows unusually fast, should be checked. You relate that almost all the frauds covered in this book could have been stopped if people had been more careful about the growth of the fraud. You add, we always face the same dilemma, do you want to reduce fraud or do you want to be rich. Have a happy evening.